À la une

À la une

Contenu en vedette

Yanick Gervais annonce son départ, Daniel Rivest sera nommé chef de la direction.

Écoutez le Coopérateur audio

Écoutez le Coopérateur audio

Notre dernière édition

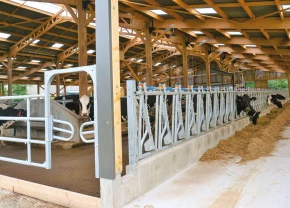

La passion agricole, construction d'étable, nouvelles variétés de semences de maïs et soya Maizex pour 2026, cultures en bandes et Filière porcine coopérative vous attendent dans votre édition de novembre!

Éditoriaux du président de Sollio Groupe Coopératif

Éditoriaux du président de Sollio Groupe Coopératif

Contenus commandités

Contenus commandités

Nos grands dossiers

Explorez nos dossiers étoffés sur des sujets d'actualité et liés directement sur votre production que ce soit par rapport à l'électricité, l'eau ou encore les marchés.

Ça bouge dans votre région!

Que ce soit pour le plaisir d’échanger ou pour élargir vos compétences professionnelles, découvrez les évènements en personne et en ligne de votre réseau coopératif.

Coopérons

Notre équipe éditoriale

Derrière les pages web et papier se cache l’équipe qui veille à la production et à la création du Coopérateur.

Faites-vous connaître

Annoncer dans le Coopérateur, c’est atteindre une communauté de plus de 12 000 membres du milieu agricole coopératif.

Faites-vous entendre

Vous avez une idée pour nous? Faites-nous en part! Nous sommes toujours à la recherche de suggestions d’articles.